I’ve always wanted to know what happened on day 1 of Post-Apartheid South Africa. What were the vibes like? What did the people get up to? Were the first few weeks of liberation a series of nationwide jubilation, or rather a huge sigh of relief to a nation that had carried a mountain of pain on its shoulders for so long? I haven’t seen any documented videos or stories on how South Africans adjusted to freedom in real time, in terms of how the freedom was processed and how it continued to live on the streets, within homes, and within hearts before the honeymoon phase wore off.

To my delight, through following the story of music in our country, I’ve come to learn that the Black South African spirit was always free; we’ve always been a people of high spirits, carried by song, always singing truth to power and harnessing the magic of music to document moments, history, and revolutions. This blog post comes two days after Kwaito Star-Group Trompies released an amapiano-infused kwaito song featuring some of the most popular names in South African music culture today. The story of South Africa continues, and the music continues to give this history a belting voice.

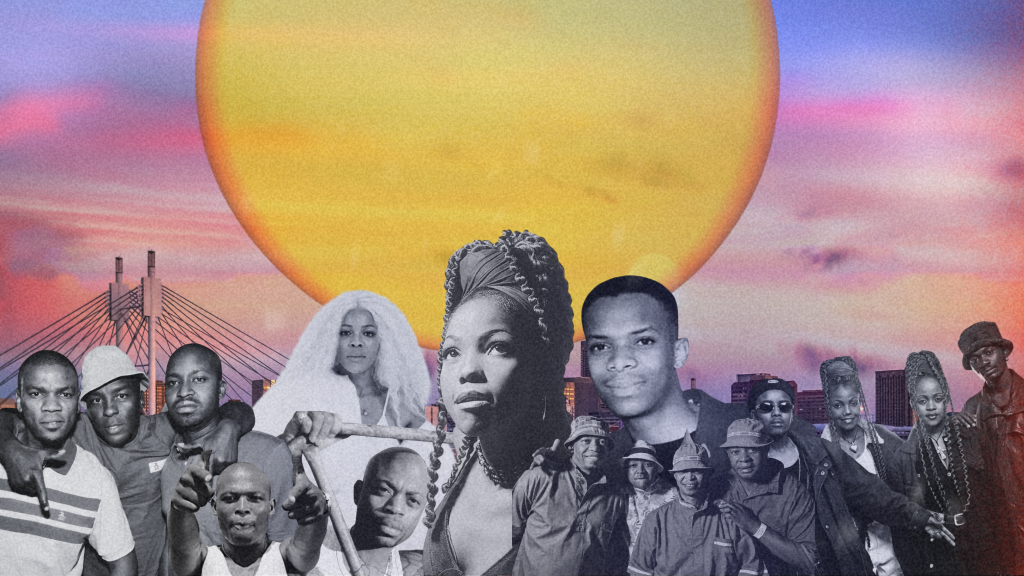

The history we reference begins in the post-1994 era, extending into the early 2000s—one generation after the Bra Hugh Masekelas, Miriam Makebas, Letta Mbulus, and Brenda Fassies of our world. We turn the page to the young and free: those who gave a liberated South Africa a new cultural language.

When Boom Shaka released “Thobela” in 1996, it was our greeting to the world with our new identity. Boom Shaka was a group of youngstars at the time who were part of the early pioneers of Kwaito music, a genre described as the melting pot of different genres that include ‘Marabi’ of the 1920s, ‘Kwela’ of the 1950s, ‘Mbaqanga’ of the hostel dwellers and ‘Bubblegum’ music of the 80’s – a host of Old South African genres while including international influences through disco music, house, hip-hop, jazz and RnB. It’s an adaptive genre that pays ode to historical South African sounds but also charts a new path for who the youth of South Africa chose to be, now free & unrestricted in their expression.

Our music remained largely political; even in the youthful Kwaito sound, we always sang for social impact. Enter the M’Dus and Trompies of Kwaito who would later influence the Brown Dashes, Mgarimbes and Thebes of South African music who sang about anything they wished to express; a true practise of and revolution into freedom. Who would have thought that the songs of the people would one day move from being about Uhuru and the yearning for freedom to being the very self-expression of and the real-time pleasures of the fruits of freedom that were fought for? M’Du’s Siya Jola (Ok’Salayo), released in 1998, marks a change of theme in South African popular music culture; this change led the way to music that was just about the day-to-day living of Black South Africans in the townships of the nation. The relaxed, colloquially charming, and culturally atuned kwaito lyrics in songs like these remain cultural pillars of the way black culture moved, what black South Africans used to say, and how they used to live. It started a preservation of heritage where the history of black people did not need to begin with pain; it could just be black joy.

On the topic of black joy, the reason why the genre was named “Kwaito” was due to its totsitaal origins, the word “Kwaito” actually means hot-tempered/angry music, derived from the Afrikaans/tsotsitaal word “kwaai”, which is another significant factor to the genre. In one of Kwaito’s most romantic songs, Brown Dash’s Vum Vum is a declaration of love, a heart-to-heart kind of song if you will, but all of this is expressed in “tsotsi” -criminal “taal”- language which carries a certain roughness and violence, in ode to the “kwaai”(anger/hot-temperedness) it is meant to reflect. The sweetest, most fun song where your boyfriend is telling you he’ll one day drive you around in a car so you can get some fresh air [the act of driving around being a luxury for the people at the time], all of this charm and sweetness expressed in a way a nonchalant, love-vocabulary-deprived, survival mode South African man from the township would express it. So Kwaito wasn’t only a music expression of freedom or a preservation of black South African culture and language heritage, it was also a cultural mirror documenting all the quirks and hopes of South Africans at a personal and family level, an Arena where black South Africans got to engage outside of politics in an arena where they existed just as humans who simply loved, had material desires, craved some fresh air and wanted to just have fun.

One classical Kwaito hit song, “Magasman” by Trompies, sits among the finest songs to ever come out of South Africa. This one particularly carries heavy jazz and RnB influences and sounds. When I think of the feeling one gets when listening to today’s Amapiano, it’s a replica of what one feels when listening to Magasman – just the most beautiful sound waves hitting your body, making you feel like you’re levitating or floating in some cool and fun sauce. This coolness and beauty in music is the essence of what makes South African music so different; it’s not only our phenomenal sense of rhythm, with songs that break structural rules of music playing onto the side of magic, but it is also the utter talent and excellence with which music is bred in Mzansi. Our music isn’t only fresh, revolutionary, and culture preserving, but it is also remarkably excellent. Trompies and many others who have made special music may not have received global acclaim and praise for their creations, but the rhythm and fusion of sounds speak of the rare and genius touch for music embodied by South African musical artists. The Apartheid government tried to dim this light when they realised Black and Coloured South Africans were making Jazz that sounds better than Western Jazz. The shadow-ban of black Jazz on government-approved TV and radio stations was meant to place black South Africans in a box to limit their capabilities. We can attest from the right side of history that the Apartheid government failed dismally in this attempt.

This revolution of Black South African Music & pride in Black South African expression was championed and completed to come full circle with the creation of TKZee by Tokollo, Zwai and Kabelo, 3 young men at the time who were products of Model-C, private school education in New Johannesburg. Their contribution to Kwaito music, and it was an immense one at that, points to the full integration of black success in the new South Africa, where the Tokollos, Zwais, and Kabelos of the world could exist in white-dominated spaces in all their truth. In one of their many hit songs, “Dlala Mapantsula,” you can actually hear their wealth of experience in the two different environments they constantly had to code-switch between. On the one hand, you can hear, for example, the twang in their “Hello December, wassup” ad-lib intro, and on the other hand, you can hear how they are able to marry that with their fluency in Kasi living and Kasi language.

House music was Kwaito music’s twin at the time, both very instrumental to the expression of a new South Africa. Here are a few of my favourite House Songs from the early 2000s as we wait for next week, to discuss a genre that married Kwaito and House music to create one of the best sounds in the world currently

KB – El Musica

Thebe – Groover’s Prayer

Leave a reply to amandampuru Cancel reply